Maui homes For Sale

- Haiku Homes For Sale

- Haliimaile Homes For Sale

- Hana Homes For Sale

- Honokowai Homes For Sale

- Kaanapali Homes For Sale

- Kahakuloa Homes For Sale

- Kahana Homes For Sale

- Kahului Homes For Sale

- Kanaio Homes For Sale

- Kapalua Homes For Sale

- Kaupo Homes For Sale

- Keanae Homes For Sale

- Keokea Homes For Sale

- Kihei Homes For Sale

- Kipahulu Homes For Sale

- Kuau Homes For Sale

- Kula Homes For Sale

- Lahaina Homes For Sale

- Lanai Homes For Sale

- Launiupoko Homes For Sale

- Makena Homes For Sale

- Maalaea Homes For Sale

- Makawao Homes For Sale

- Maui Meadows Homes For Sale

- Molokai Homes For Sale

- Nahiku Homes For Sale

- Napili Homes For Sale

- Olinda Homes For Sale

- Olowalu Homes For Sale

- Paia Homes For Sale

- Pukalani Homes For Sale

- Spreckelsville Homes For Sale

- Ulupalakua Homes For Sale

- Wailea Homes For Sale

- Waihee Homes For Sale

- Wailuku Homes For Sale

Hawaiian Moment The Big Island or Maui Nui

When most people think of the Hawaiian Islands, they picture the familiar eight that make up the modern chain. Yet, long before the islands took on their current form, a much larger island once existed in the central Hawaiian archipelago. Known to geologists as Maui Nui, or “Greater Maui,” this prehistoric landmass was a massive island formed from seven shield volcanoes.

In Hawaiian, nui means “great” or “large.” The concept of Maui Nui was first proposed over sixty years ago by geologist Harold Stearns, who recognized geological evidence of repeated episodes of island submergence and reemergence. His early observations laid the foundation for what modern researchers now understand about the dynamic evolution of the Hawaiian Islands.

According to the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO), Jonathan Price of the Smithsonian Institution later advanced this concept by modeling the area’s submergence history using computer-based Geographic Information System (GIS) technology. His models examined the effects of global sea-level change, the ages of the volcanoes, and the likely rates of volcanic subsidence.

The HVO explains that during its prime, around 1.2 million years ago, Maui Nui covered approximately 5,640 square miles—about 50 percent larger than today’s Big Island of Hawaiʻi. The ancient island included what is now Penguin Bank, a broad shallow area west of Molokaʻi.

Over time, the immense weight of the volcanic mountains caused the Earth’s oceanic crust beneath them to bend downward. This process, known as subsidence, occurs as the crust bows under the added mass of lava from the Earth’s mantle, sinking at rates of more than 3 millimeters per year (roughly 0.1 inch annually). As volcanic activity diminished, the lower regions or “saddles” between the volcanoes became submerged. Gradually, the once-unified island separated into distinct landmasses.

Another key factor in this transformation was global sea-level change, influenced by the growth and melting of continental glaciers. While subsidence steadily reduces an island’s size, changes in sea level can either enlarge or diminish it. When glaciers expand, sea levels drop, exposing more land. Conversely, when glaciers melt, sea levels rise, submerging low-lying areas.

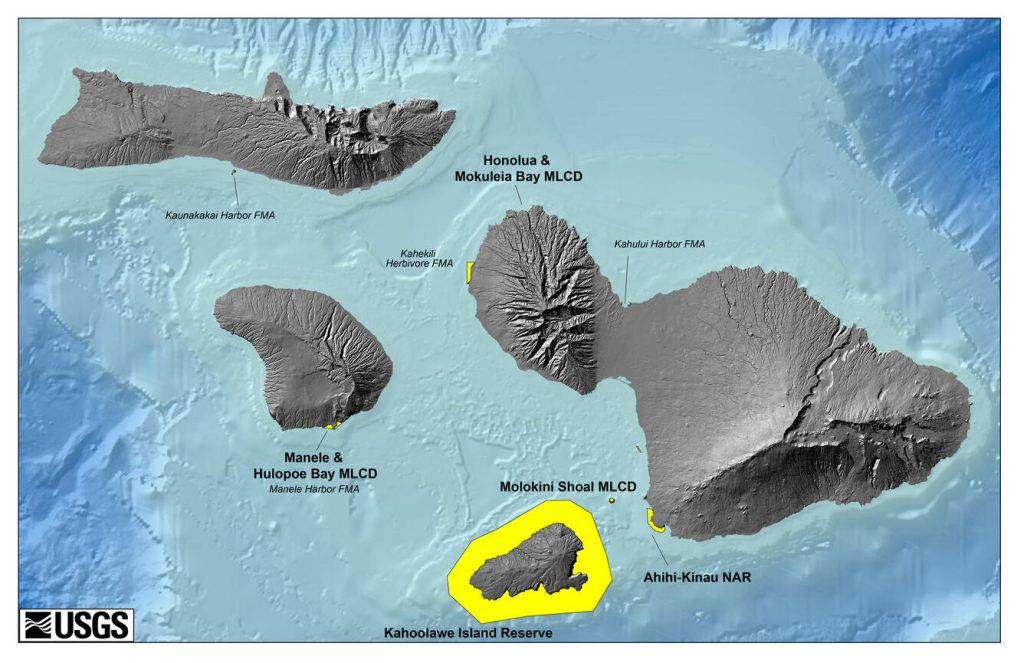

Today, with much of Earth’s ice long since melted, sea levels are higher than at nearly any point in the past 200,000 years. This has left behind four islands that were once part of ancient Maui Nui: Maui, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe.

The sea floor between these islands remains relatively shallow—around 1,600 feet deep—but at the outer edges of the former Maui Nui, it plunges dramatically into the abyssal depths of the Pacific Ocean, reaching 28,000 feet below sea level.

Administratively, the islands that once formed Maui Nui are today united under Maui County. What was once a single grand island is now a cluster of distinct yet geologically connected landscapes, each carrying a piece of Hawaiʻi’s deep volcanic past.